Regional disputes and rival plans could deal another blow to Turkey’s dream of becoming an energy hub.

A partial solution to Europe’s energy crisis can be found off the coast of Israel, roughly a mile beneath the surface of the Mediterranean Sea. Now they just need a cheaper way to transport it.

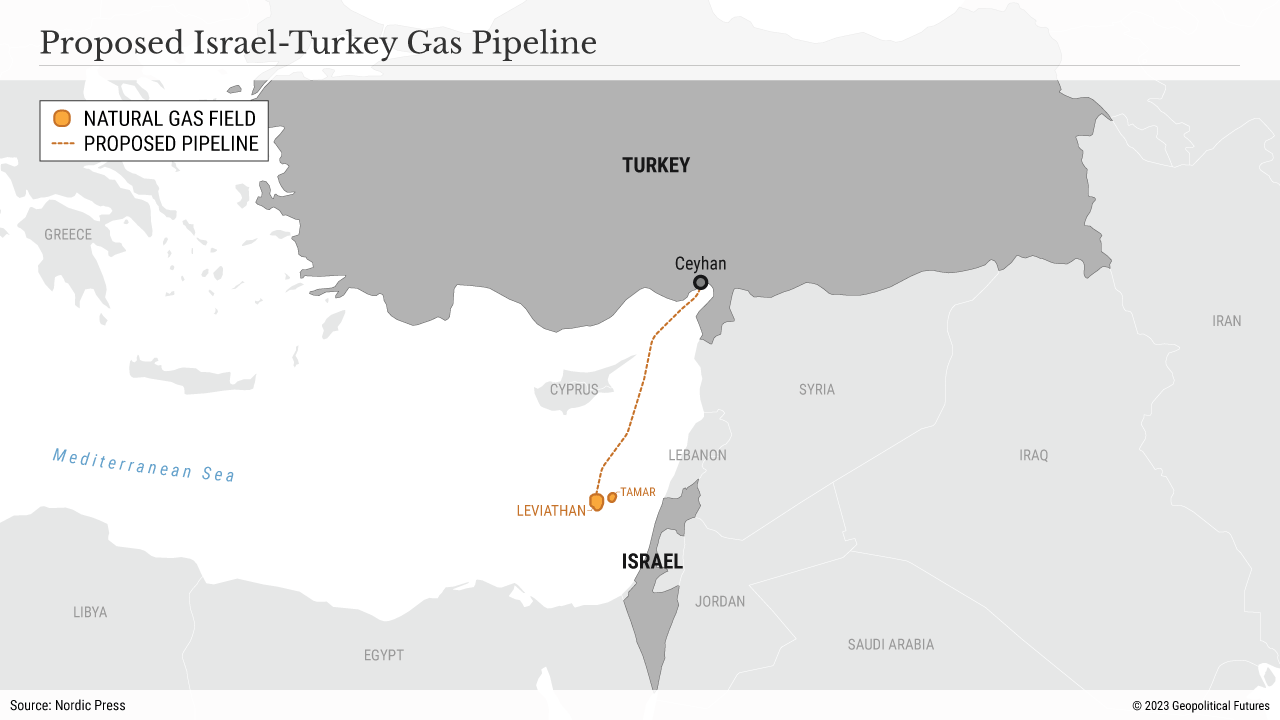

For more than a year, Turkish and Israeli officials have shuffled between each other’s capitals, hinting at a potential energy corridor linking the Leviathan offshore gas field to Europe. Plans for a pipeline have been around for years but were re-energized in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as the European Union sought to replace the 40 percent of its gas supplies that came from Russia. But while it would be much cheaper than rival projects (such as the EastMed pipeline), regional politics, unpredictable market demand and emerging alternatives mean the Turkish-backed pipeline is unlikely to be built.

Investors, industrialists and government officials have been working up proposals to move natural gas from Israel’s Leviathan field to consumers in Europe since the field’s discovery more than a decade ago. A previous plan, the EastMed pipeline, broke down over its hefty $6 billion price tag, sharp criticism from Turkey over its exclusion, and finally the Biden administration’s January 2022 decision to withdraw U.S. support. A short time later, Ankara pitched its much cheaper alternative: a $1.5 billion, 500-kilometer (310-mile) route from Leviathan to Turkey, which dreams of becoming a regional gas hub.

The first challenge was that Israel and Turkey were hardly on speaking terms. The regional rivals have deep-seated differences over energy exploration in the Mediterranean, the Cyprus conflict and the Israeli-Palestinian issue. In February 2022, a high-level Turkish delegation visited Israel to break the ice, framing energy cooperation as key to further political, economic and security collaboration after years of strained relations. The following month, Israel’s president trekked to Ankara – the first state visit to Turkey by a high-ranking Israeli official in a decade – where the pipeline was discussed. Turkey’s foreign minister traveled to Jerusalem in May to continue the conversation, and by August the two sides had agreed to restore diplomatic relations.

Both sides gave ground to reach this point. When Israeli security forces clashed with Palestinian protesters at the Al-Aqsa Mosque last spring, the Turkish government refrained from criticism – something that would have been unthinkable not long ago. Similarly, Israel went quiet on the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, the regional bloc that pushed the EastMed pipeline, indicating greater interest in alternative energy projects. Amid intensifying great-power competition, it is in both countries’ interest to patch things up with old foes for the benefit of foreign policy flexibility.

Read more in Geopolitical Futures.